Symptoms, Scans, and Self-Advocacy: Three years with Cholangiocarcinoma

Trusting my Body, Challenging the System

Introduction: A Journey of Resilience

On World Cholangiocarcinoma Day—three years to the day since my diagnosis—I invite you to walk with me along the winding path of my illness: from the earliest whispers in my body to the thunderclap of diagnosis, and through the maze that followed.

This post is meant to help any of you making your way through the often bewildering corridors of the U.S. healthcare system. It’s also a call to those living with unanswered questions in their bodies: trust what you feel. Speak up when something feels off. Push when the system tells you to wait

Too often—especially if you are a woman or a person of color—your knowing is dismissed, your symptoms minimized, your urgency met with delay.

I share this story in the hope that it offers you something useful: insight, language, or simply the reminder that you are not alone—whether you’re the one in the exam room or the one holding a loved one’s hand.

Early Warning Signs: Piecing Together the Puzzle

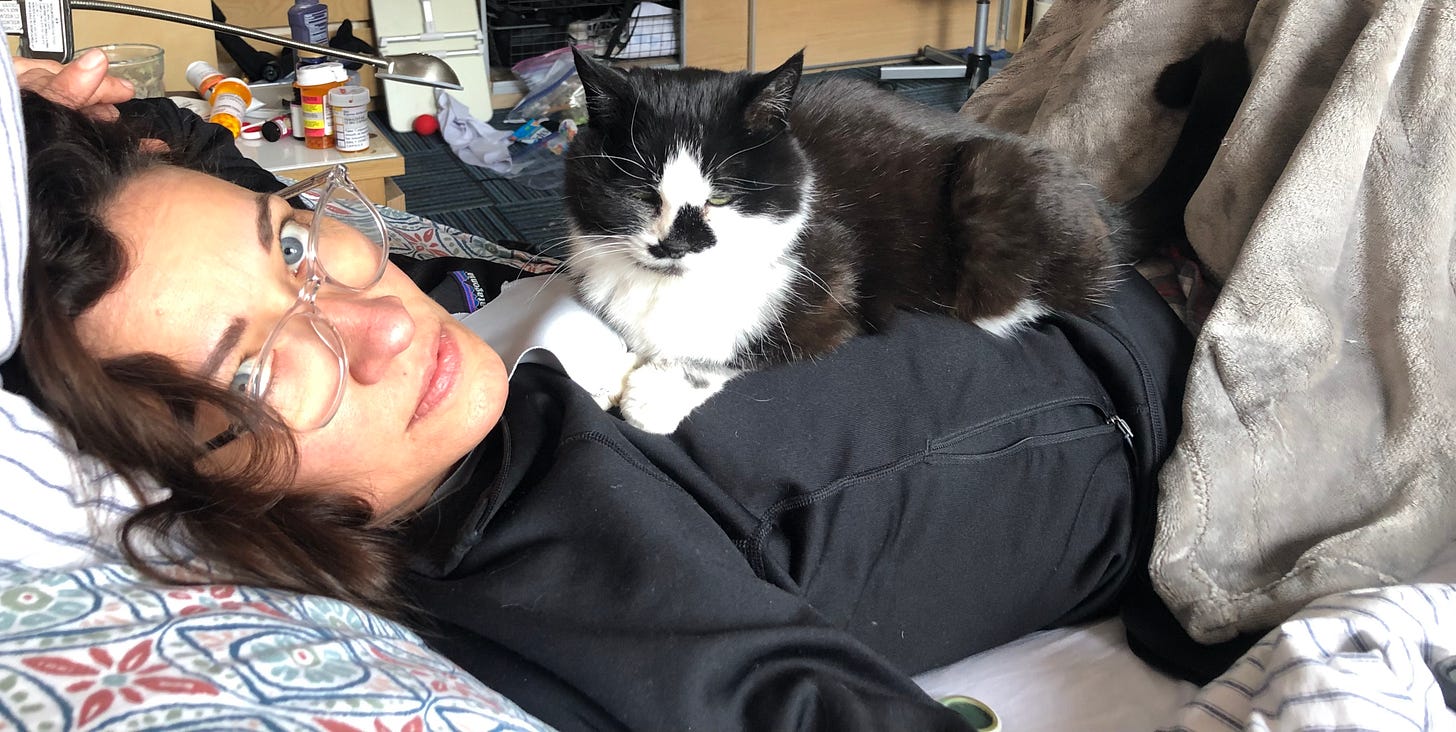

Three years ago, my life veered into the realm of terminal illness. There was no dramatic event—just a slow accumulation of seemingly unrelated symptoms that ultimately led me to a rustic clinic tucked into the Vermont mountains.

For nine months, the signs built gradually. Fatigue crept in. Shortness of breath dulled the joy I once found in yoga, cycling and other physical activities. My once robust appetite faded, triggering unexpected weight loss. Then came migraines—new and intense—accompanied by waves of nausea that contrasted sharply with my usual energy. Each symptom alone seemed manageable, but together they formed a pattern I could no longer ignore.

The Diagnostic Odyssey: A Maze of Medical Mysteries

In search of answers, I entered what felt like a revolving door of specialists, each examining a single piece of the puzzle but missing the full picture. Test after test zeroed in on isolated systems—neurology, gastroenterology, gynecology—each returning the same verdict: unremarkable—a term that now holds a permanent place in my personal lexicon of medical irony.

With no answers in sight, I took matters into my own hands. I asked for an upper endoscopy, but the backlog from the pandemic meant long delays. In the meantime, an elevation in my liver enzymes was casually noted. My doctor, reassured by my long track record of good health, suggested we check again in a few months. No urgency. No alarm. Just a gentle pat on the back and the assumption that all would be fine.

I clung to that logic too. Maybe it was early menopause. Or long COVID. Or just the natural wear of middle age. I told myself it could wait.

But looking back, I wish I had insisted. I wish I had demanded that endoscopy, or sought out urgent care when the migraines and nausea became relentless. At the time, the delays felt like external obstacles—pandemic protocol, triage logic, a cautious system doing its best. But together, those deferrals added up to a silence that allowed something serious to continue undetected.

Now I see how the system’s fragmented approach, combined with my own well-practiced stoicism, let the warning signs go unheeded. And how the comfort of being told not to worry can sometimes be the most dangerous diagnosis of all.

A Vermont Turning Point: When the Body Speaks Louder

It was President’s Day weekend, three years ago. My partner and I had driven up from Washington, D.C., trading city noise for Vermont’s quiet, snow-blanketed stillness. The trip was meant to be a restorative pause—a chance to see family, breathe crisp mountain air, and shake off the lingering malaise I’d been quietly carrying for months.

I hadn’t felt well, but I told myself it was nothing serious. Just another ripple in the string of unexplained symptoms I’d started to normalize. But by the second night, something changed. A strange itch began on the soles of my feet—deep and unrelenting, keeping me awake. Then, just as abruptly, my urine turned the color of dark tea. These weren’t symptoms I could explain away anymore. My body was trying to tell me something, and this time, it was speaking in a voice I couldn’t ignore.

Like many, I turned to the internet for answers. Gallstones seemed the likely culprit: uncomfortable, but treatable. A telehealth doctor agreed that an ultrasound was warranted.

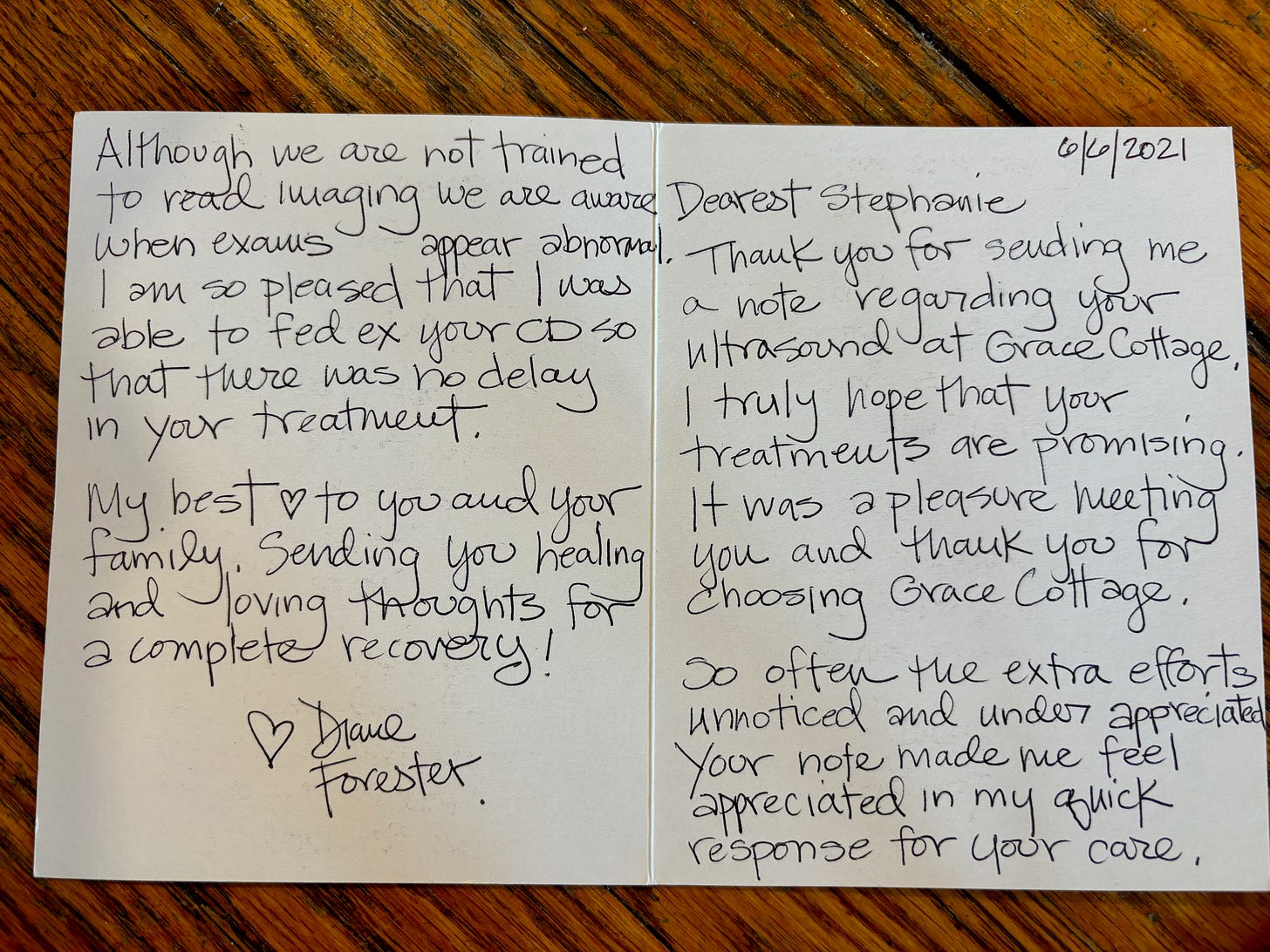

In rural Vermont, on a holiday weekend, that was easier said than done. After a few calls, I found myself driving down snow-dusted roads flanked by pine trees to Grace Cottage Hospital. The building looked more like a converted farmhouse than a medical facility—simple, welcoming, intimate. Inside, the atmosphere was quiet and reassuring. Walking in, I felt less like a patient and more like a family guest.

That warmth carried into the ultrasound room, which felt less like a sterile exam space and more like someone’s den. Framed family photos and keepsakes lined the technician’s desk, softening the presence of the machine beside us.

She greeted me with easy familiarity, chatting about her kids and life in Vermont during the pandemic. When I mentioned I was worried about gallbladder trouble, she nodded sympathetically and shared her own experience with gallbladder surgery—how straightforward it had been, how much better she felt afterward. Her story, offered without fanfare, made the unknown feel briefly manageable.

But once the scan began, something shifted. The conversation trailed off. Her friendly chatter gave way to silence, and her gaze grew focused, serious.

She guided the probe beneath my right ribcage, gently at first. Then again. And again—each time pressing harder. The pressure was sharp now, physical and emotional. She hovered over the same area, adjusting angles, reapplying gel, clicking quietly each time she paused. The screen was turned away from me, so I couldn’t see what she saw—only hear the small, deliberate sounds that marked each image she captured.

The room had grown still. What had begun as routine now felt anything but.

As I gathered my things to leave, the warmth of our earlier exchange had vanished. I searched her face for some flicker of reassurance—a smile, a casual “looks good”—anything to ease the growing knot in my stomach. I knew she wasn’t allowed to share results, but still, I hoped.

Instead, she offered only that the images would be sent to my doctor in D.C. by FedEx right away—expedited. That word alone told me more than she was willing to say.

The shift was unmistakable. The easy rapport had been replaced by clinical formality, and what wasn’t said hung in the air, heavier than words. It was the kind of silence that leaves a mark.

Outside, the cold Vermont air bit at my face. On autopilot, I reached for my phone to resume a media interview I’d paused earlier—grasping at the illusion of control, of normalcy, as something unnamed and enormous gathered on the horizon.

The next day, my primary care physician called. Normally warm and familiar, his voice was subdued. He got straight to the point: the ultrasound had revealed sizable masses on both lobes of my liver. At the bottom of the radiologist’s report was a phrase that landed like a blow: “Findings are concerning for underlying malignancy.”

The language was clinical but the message was unmistakable. Still, I held fast to a fragile hope: maybe it was something operable. Maybe they could just cut it out. Maybe a few rounds of chemo would follow, and then I’d be okay.

I had no idea that this call marked the start of a far more complicated story—one that would rewrite the story I thought I was living.

A Name, and a New Reality

By Monday morning, back in D.C., I was swiftly absorbed into the rhythm of the medical industrial complex—positioned inside the sterile cradle of a CT scanner, a space that would become unnervingly familiar. The report was restrained, but unflinching: two sizable liver lesions, “likely cholangiocarcinoma,” along with necrotic lymph nodes and dilated intrahepatic bile ducts. The words didn’t need embellishment. What they pointed to was clear—something serious had taken root, and it had been there for some time.

That was the first time I heard the word cholangiocarcinoma—a diagnosis so rare that even many doctors have never encountered it. Within hours, it became the axis around which my life began to spin.

It was also the moment the internet turned from a source of information into a portal of dread. The statistics were bleak: most patients die within a year. The five-year survival rate barely cracks two percent. Surgical removal—the only curative option—carries a 75% chance of recurrence. The numbers didn’t feel abstract. They felt personal. They felt immediate.

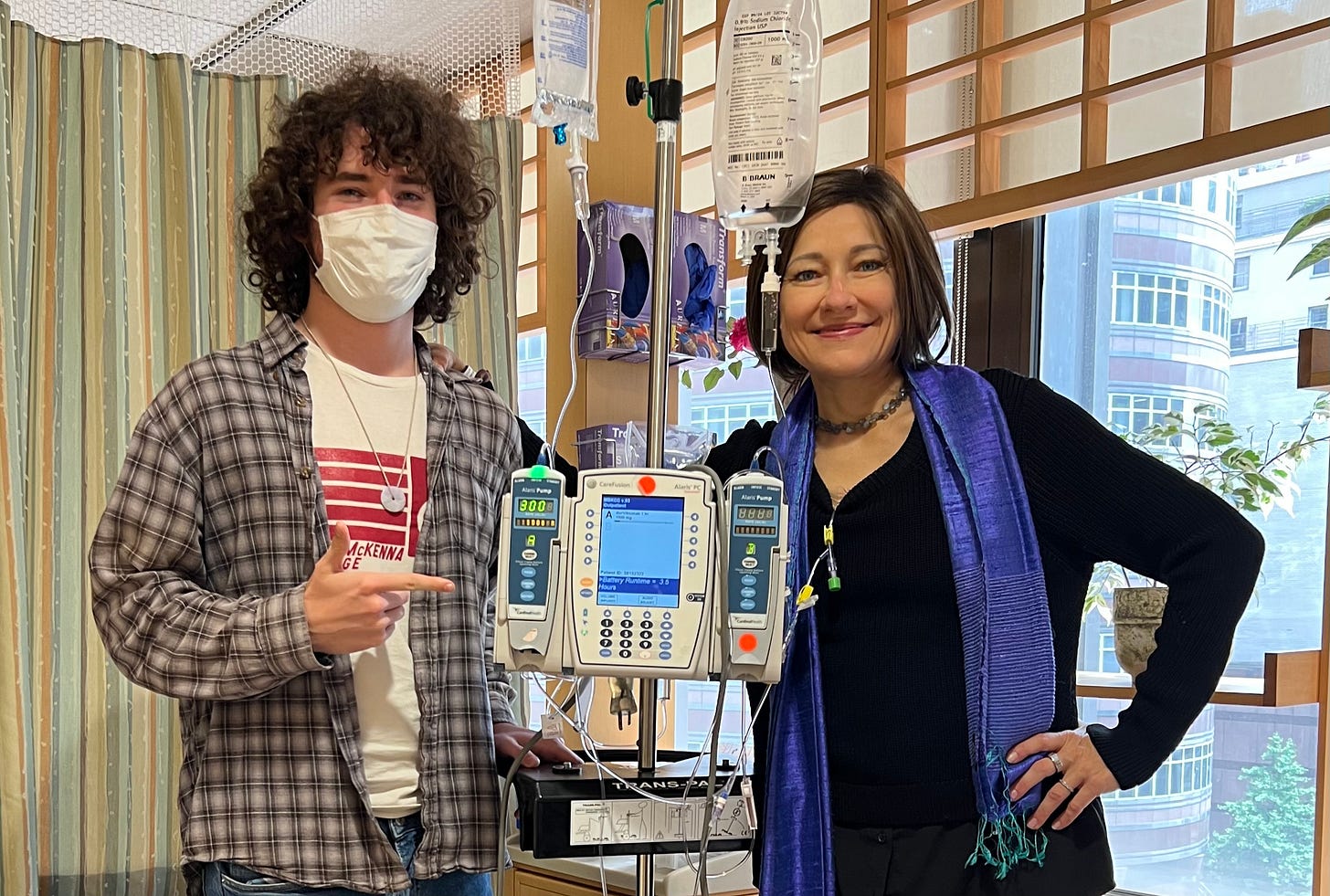

Initiation into the World of Oncology

Less than a week later, I found myself in the waiting room at Memorial Sloan Kettering for a 7 a.m. consult with one of the country’s top cholangiocarcinoma specialists. There was little space to process, no moment to pause. The focus was triage: lower dangerously high calcium levels, order a cascade of scans, schedule a liver biopsy, insert a Mediport. I had been swept into the current of oncology, where events unfolded with a rhythm that felt both urgent and oddly routine.

The biopsy procedure, described as “minimally invasive,” provoked a disproportionate response—searing pain, a sudden fever, and an unplanned trip to the emergency room. After ruling out anything serious, the surgeon offered a wry summary: “The liver doesn’t like to be poked.”

It was a moment of dark humor—but also a reminder. Cancer had picked a fight with one of my body’s VIP organs. From that point on, nothing about this would be simple.

Worst case scenario: Stage 4, Inoperable, Incurable

Though it would take weeks for the official pathology to come back, the scans left little room for doubt: stage 4 intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Inoperable. Incurable. The primary liver tumor measured 13 by 11 centimeters and had already spread to regional lymph nodes. More troubling still, it had invaded the left and middle hepatic veins and was compressing the portal vein—an anatomical chokehold.

Months later, a radiation oncologist underscored the precariousness of the situation with a single fact: just two millimeters of vasculature were responsible for draining my entire liver. If that fragile passage closed, he warned, it could trigger “a heart attack of the liver.”

A Mutation, Inheritance, and a Mother’s Prayer

I was 51. The median age at diagnosis for cholangiocarcinoma was 70. I didn’t fit the profile. I searched my past for clues. Could it have been liver fluke disease from raw fish eaten during many years traveling through Asia? Tests ruled that out. I considered the heavy pollution during our time in China. Then a new possibility emerged: a rare hereditary mutation called BAP1—something I carried and hadn’t thought much about until then.

Historically, the BAP1 mutation hadn’t been linked to cholangiocarcinoma. But an MSK genetic counselor mentioned something curious: a noticeable uptick in patients with this rare mutation being diagnosed with the disease. Since then, research has confirmed what we suspected—there is, in fact, an association between BAP1 mutations and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. The list of cancers tied to this mutation is growing, and so is our understanding of how it operates.

When I learned of the link, I had my son tested. Unfortuantely he carries the BAP1 germline mutation too. That knowledge sits heavy in my chest, but he’s already begun early screenings. I hold a quiet hope, a mother’s prayer, that by the time he’s older, medicine will have caught up—the science will have advanced—and that this genetic thread won’t bind his future the way it has mine.

The Silent Epidemic: Cancer's Quiet Advance in the Young

Cholangiocarcinoma has long been considered a disease of the elderly, but in my support groups, a different pattern has emerged. More and more, I encounter people in their 30s and 40s—too young, too healthy-seeming—suddenly grappling with advanced diagnoses. At first, I thought it was anecdotal. But the numbers suggest otherwise.

This isn’t unique to cholangiocarcinoma. Across cancer types, oncologists are seeing an unsettling rise in diagnoses among younger adults. Researchers are still unpacking the reasons, but one likely factor is the steady accumulation of environmental carcinogens in our daily lives—microplastics, PFAS, air pollutants, and chemicals that were once invisible and are now unavoidable. Recent studies and deeply reported pieces point to a broader epidemiological shift that our systems have yet to catch up with.

The need for younger people to proactively seek medical testing can’t be overstated—especially in a system that often fails to see them. When cancer is still largely viewed as a disease of the old, younger patients fall through the cracks. Symptoms are waved off as stress, diet, anxiety, or “just getting older.” Diagnoses come late—often, too late.

A survey by the Colorectal Cancer Alliance revealed that many younger patients were misdiagnosed multiple times before receiving a correct diagnosis. Their symptoms were real, but the system wasn’t built to recognize them. It’s a pattern I’ve seen echoed in support groups and my own experience: the burden of proof falling on the patient, the urgency dulled by misplaced reassurance.

This reality demands vigilance. It demands that younger people trust what they feel in their bodies, challenge assumptions, and keep pushing when the answers don’t make sense. In a healthcare system calibrated for probabilities, sometimes the only way to be seen is to insist on it.

Treatment Trenches: Chemotherapy, Side Effects, and Self-Advocacy

The cancer had already threaded into my portal vein and spread to nearby lymph nodes. Because cholangiocarcinoma spreads early and insidiously, surgery is only an option if the disease is caught before it extends beyond the liver. Mine had already spread. So the diagnosis was deemed inoperable—and with that, incurable. Remission was off the table. The only path forward was palliative.

I started chemotherapy—cisplatin and gemcitabine—the standard first-line treatment for advanced cholangiocarcinoma. To my relief, the regimen shrank the tumor slightly and brought two years of precious stability. In this disease, where median survival is often measured in months, that counted as a win.

When the cancer eventually adapted, as aggressive cancers do, I shifted to Pemigatinib, a targeted therapy that hadn’t yet been approved when I was first diagnosed. It’s designed for patients with FGFR2 fusions, a rare genetic alteration that my tumors carry. I’ve now been on it longer than the average nine-month window of effectiveness—another quiet defiance of the odds.

The Life-Saving Power of a Second Opinion

When a scan last year showed modest tumor progression, I did what many patients hesitate to do—often out of fear, loyalty, or sheer exhaustion: I sought a second opinion. It turned out to be one of the most pivotal decisions of my entire treatment journey.

At MD Anderson, a top specialist in cholangiocarcinoma reviewed my case and saw something others had missed: I was an ideal candidate for high-dose ablative radiation to the liver, treating the cancer locally in addition to my systemic chemo. The technique had been developed at MDA by Dr. Christopher Crane—who had recently brought the protocol to Memorial Sloan Kettering, where I was already receiving care.

Back in New York, I met with Dr. Crane. Within weeks, I was receiving a cutting-edge treatment that had been available at my very same hospital all along—yet no one had mentioned it. It wasn’t a question of access or resources. It was a failure of internal communication, yes—but also a failure of imagination. My primary oncologist had been cautious, perhaps overly so in pursuing only systemic chemotherapy. In a system trained to follow protocol, the possibility of something more aggressive had never entered the conversation. Even at the best institutions, innovation can get buried beneath hierarchy and habit.

What followed was rare: genuine collaboration between specialists who had hardly spoken before. The hope is that these local treatment options will now become more available to other MSK patients. But had I not stepped outside the institution for a second opinion, I never would have known this potentially life-extending therapy was an option at all.

Second opinions aren’t just wise—they can be lifesaving. They validate diagnoses, reveal overlooked options, and connect patients to new clinical trials or better-matched care teams. Most insurance plans cover them, though it’s smart to confirm the process in advance.

Above all, seeking a second opinion is an act of self-advocacy. It can shift the trajectory of a disease. And a good doctor will not only accept that—it’s what they want for you.

Walking the line: Balancing between Life’s Length and Depth

The time these treatments have bought me has come at a cost. In many ways, the side effects of cancer therapy can eclipse the symptoms of the disease itself, creating a constant tension between prolonging life and preserving its texture.

I’ve chosen to prioritize quality over quantity—a decision that requires ongoing negotiation with my medical team. Oncology, by nature, is built around life extension. But I’ve had to advocate for the integrity of my life, again and again: requesting dose reductions, pausing steroids, adjusting treatment timelines to match my energy levels and the contours of real life.

Sometimes, those requests were dismissed or delayed—lost in a system not built for nuance. More than once, treatment was set to move forward as planned, despite my concerns, until I intervened. Those moments made it clear: vigilance isn’t optional. It’s not enough to speak up once. You have to follow up, push back, and keep pressing until your voice reshapes the plan.

Legal tools like advance directives can help ensure that your preferences are honored—especially as you approach end-of-life decisions. In a future post, I’ll share more about the DNR I’ve chosen to put in place, and how I’ve come to define what a good death means to me.

Video: This small Neulasta device boosts white blood cell counts after chemo—but carries its own burden of side effects, including bone pain, headaches, nausea, fatigue, fever, and dizziness.

Hospital Hurdles: Advocacy in the Eye of the Storm

Advocating for yourself in the hospital is both essential and extraordinarily difficult. The system is built on specialization—each doctor focused on one part of the puzzle, rarely stepping back to consider the whole. And just when you most need to speak up, you’re often least able to: physically depleted, sleep-deprived, and enveloped in a mental haze. That fog—known as hospital-induced delirium—can distort time, memory, and even identity. It’s especially common in intensive care or during extended admissions.

Before cancer, my only hospital stays had been short, usually overnight, following orthopedic surgeries. But over the last three years, every admission has brought with it a stretch of cognitive disorientation—an eerie reminder that in moments of acute vulnerability, even asking for what you need can feel like climbing a mountain in the dark.

During one stay for a bile duct blockage, I remained hospitalized long after I had begun to recover. As the mental fog cleared, I remembered: I was supposed to be in Peru the next week. Yet my team of eight physicians wasn’t even discussing discharge. They were still running tests, hesitant to move forward, stalled by bureaucracy more than biology. So I asked directly: “What exactly needs to happen for me to be released?” They gave me a list. I tackled each item systematically—and walked out in time to get my plane.

On another admission, I was caught in a loop: four consecutive days of fasting, each in preparation for a delayed procedure to investigate a possible blockage. At a hospital like MSK, which treats many patients in far more unstable condition than I was, I seemed to fall lower on the priority list. No one said it outright, but the message was clear. Meanwhile, the repeated fasting left me so weak I could barely stand—at a time when the cancer already made it difficult to eat or maintain weight, a condition known as cachexia. And still, no one was appreciating the risk. By the fifth day, I drew a line. I told my doctors I would decline the procedure if it was postponed again

That’s when they pivoted to an MRI—non-invasive, fast, and basically just as effective. It avoided not only further delays, but the risk of post-procedural pancreatitis. It had always been an option; it just hadn’t been offered.

That experience revealed a sobering truth: sometimes the safer, smarter path exists—but it takes the patient to ask for it. In a system overrun by caution, complexity, and compartmentalization, clear, direct self-advocacy can be the difference between stagnation and forward motion.

Confronting Healthcare's Fragmented Reality

Reflecting on my journey—from the earliest whispers of symptoms to the stark reality of this diagnosis—I sometimes wonder if things might have been different had I pushed harder at the very beginning. Instead of insisting on answers, I moved at the pace of the system, deferring to timelines and protocols. What if I had demanded that endoscopy sooner, or insisted on a scan when my liver enzymes were elevated? Could an earlier diagnosis have opened a window for surgery—while it was still possible? I’ll never know.

The fragmented nature of the U.S. healthcare system played a pivotal role in the delay of my diagnosis. Each symptom—migraines, nausea, fatigue, liver enzymes—was treated in isolation. A neurologist ordered a brain scan. A gynecologist ordered an ultrasound. A gastroenterologist performed a colonoscopy (bypassing the liver entirely). While each specialist acted within the bounds of their training, no one connected the dots. This compartmentalized approach overlooked the bigger picture: me as a whole person. I long for a medical model that recognizes the complexity and interconnectedness of our bodies. Until then, I continue to seek healing in complementary approaches that reach beyond the limits of conventional care.

Additionally, the insurance system often dictates care based on rigid algorithms, incentivizing or denying tests and treatments in ways that defy individual nuance. My case repeatedly fell outside their formulas—I’ve been denied essential scans, treatments, procedures and medications. But we are not statistics. No algorithm can capture the complexity of a human life.

The lessons of the past three years have made me a fiercer advocate for my own care. Navigating doctors, medical offices, and repeated insurance denials has demanded constant vigilance and persistence. Taking ownership of my healthcare has been a way to reclaim agency in the face of illness. But it can be exhausting. And for those unable to track every detail, the system can be even more overwhelming—highlighting the vital role of caregivers and the urgent need for a healthcare system that centers patients, not bureaucracy.

Cancer is a Team Sport: Finding Strength Together

I’ve also drawn strength from community—especially the connections I’ve made with fellow patients in the cholangiocarcinoma world and beyond. Together, we’ve built a network of shared wisdom, mutual encouragement, and collective advocacy for greater awareness and research. The Cholangiocarcinoma Foundation has been instrumental in nurturing this sense of belonging, while also supporting a growing network of doctors and researchers accelerating progress in meaningful ways. I’m looking forward to reuniting with my fellow cholangio “warriors” at this year’s annual meeting. While I’m uneasy with battle metaphors, standing alongside others in these turbulent waters has given me a deep sense of purpose, courage, and solidarity.

Another form of empowerment I’ve claimed is refusing to let this disease define the entirety of my existence. Despite the relentlessness of the cancer and the demands of its treatment, I’ve made a deliberate choice to confine my identity as a patient to medical settings. Even within those walls, I remind myself of all the roles I play beyond my cancer patient role. By consciously reclaiming my fuller self, I remain committed to living as richly and expansively as possible, beyond the boundaries of appointments, infusions, and hospital beds.

Cancer takes so much—it chips away at what makes life feel full, vibrant, and free. But I am determined not to let it take the parts of me that matter most: the roles I cherish, the love that sustains me, the joy I still find. This isn’t a denial of my reality or the weight of my diagnosis; it’s an act of defiance and devotion—a way of affirming that my life holds worth and meaning no matter how much time remains. It’s a path not only of survival, but of living with clarity, intention, and a steady embrace of the light and the shadows.

A Call to Action and Reflection

Reflecting on my journey with cholangiocarcinoma, I recognize how deeply individual experiences can illuminate broader systemic failures—and possibilities for reform. My story is uniquely mine, but it echoes countless others, especially among women, BIPOC communities, and anyone who has been dismissed, delayed, or devalued within the healthcare system. The call for change is not abstract—it’s urgent, it’s tangible, and it’s personal.

Decades of research confirm that health disparities are not accidental. Studies show that women and racial minorities are more likely to have their pain undertreated, their symptoms overlooked, and their diagnoses delayed. The consequences are profound: later-stage diagnoses, reduced treatment options, and worse outcomes. For rare diseases like cholangiocarcinoma, these inequities are magnified by lack of awareness, siloed care, and insurance systems that prioritize algorithms over human complexity.

That’s why we must become active participants in our care. Bring someone with you to appointments. Track everything—every lab, every bill, every question. Learn your insurance coverage as if your life depends on it—because it might. The system is not designed to catch us. Too often, we must catch ourselves—and each other.

With knowledge, we gain power: the power to question, to challenge, and to change. When we connect with others navigating similar terrain, we build more than community—we build momentum. Our individual voices, amplified together, become a chorus that can no longer be ignored.

But awareness alone is not enough. Real transformation requires action. Support evidence-based policies that protect patients. Advocate for funding that accelerates research, especially for rare and underfunded diseases. Share your story—not just to be heard, but to help others feel less alone and more prepared.

As we move forward, may we be fierce advocates for our own care, vigilant allies for those whose voices have gone unheard, and unwavering in our belief that compassion belongs at the center of medicine. Together, we can turn lived experience into lasting change—replacing silence with solidarity, and suffering with purpose.

We may encounter many defeats but we must not be defeated. - Maya Angelou

Fascinating informative : both practical and personal ! Your ability to convey information via the written word is amazing!

Thank you for being so generous with your, time, your, life, and your experience told so vividly. Not only a great read but the information is so valuable. I could never even begin to imagine fighting for myself within this broken medical system. Thank you for hi-lighting self advocacy.